He Reads Didion, But...

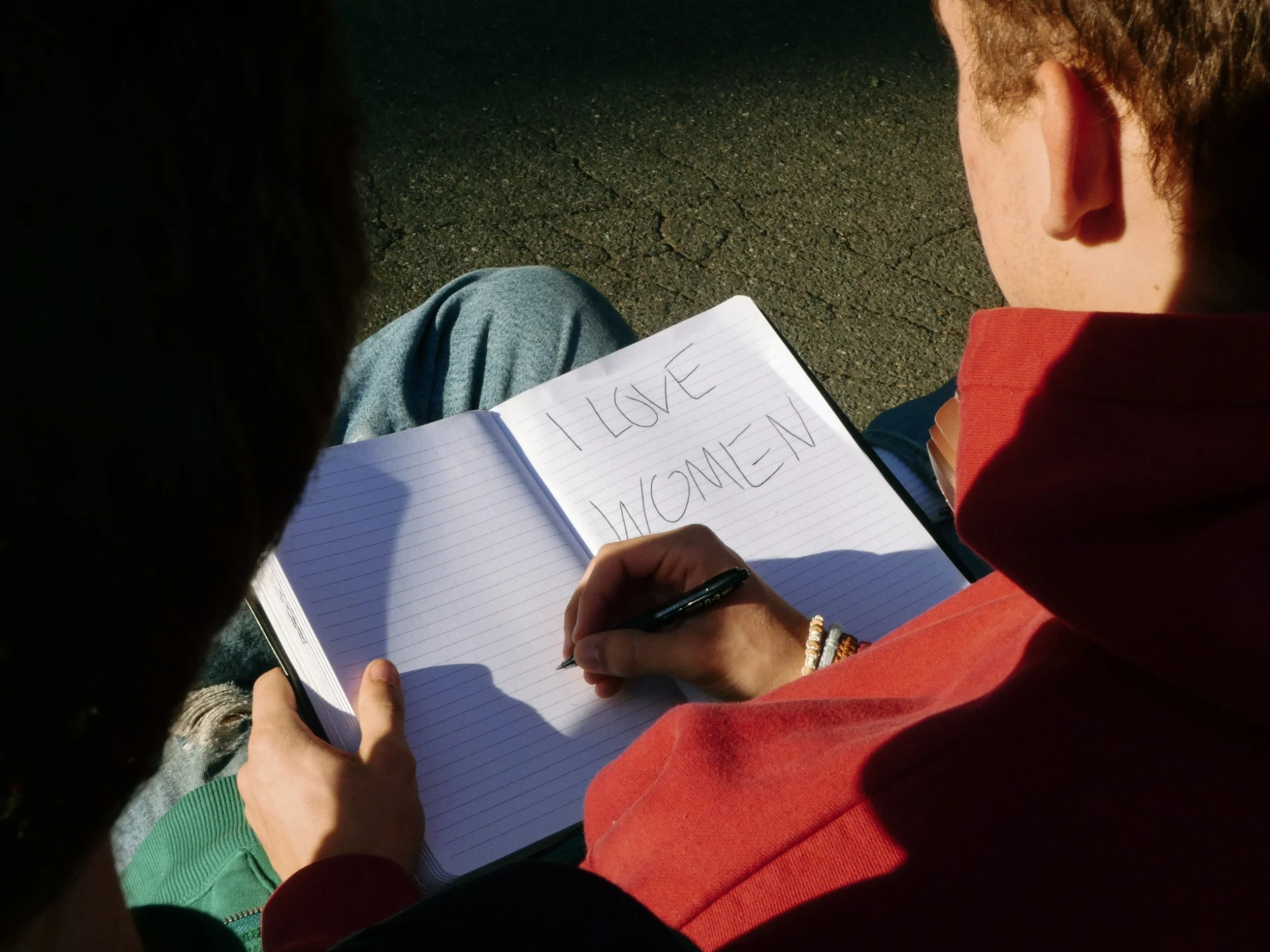

He reads didion, but…

Written by kat boskovic

Photographed by Jaqui Debonis

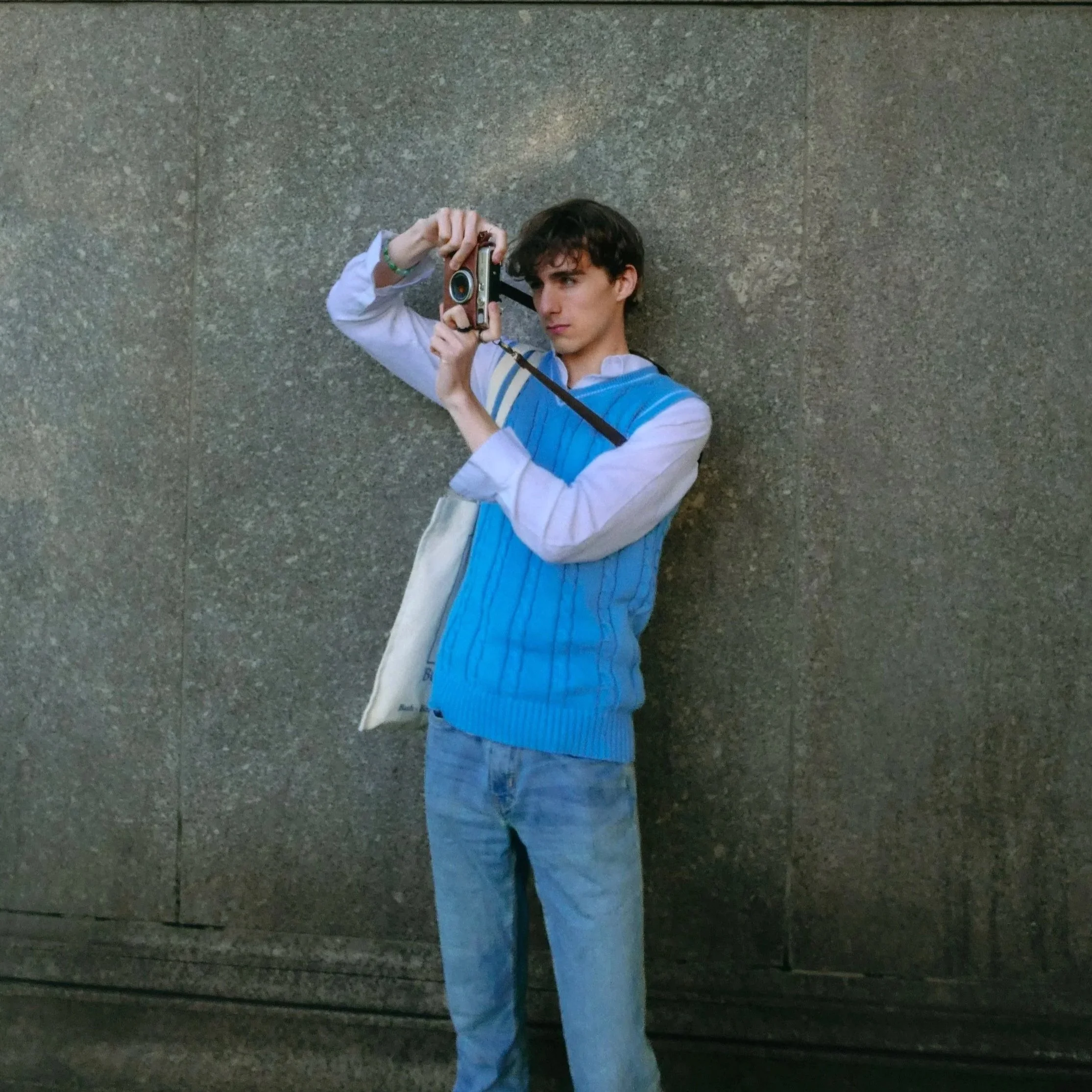

I met him first in Barcelona, in the dim light of a friend of a friend’s apartment. He wore a cropped graphic t-shirt and baggy jeans, his nails were painted black, and each knuckle displayed a different thrifted ring. We talked about reality television, as Love Island had just finished, but the conversation rapidly spiraled into a heated debate regarding the free use of filler injections. That’s when it dawned on me that I had encountered the star of the various contests across the country, from New York City to Seattle: the performative man. Here was a man who, despite his blatant ignorance of various feminist ideologies, performed sophistication and sensitivity with immense conviction. And he somehow believed this performance was radical.

The joke of the performative man circulates widely: TikTok memes, “performative man” competitions, and think pieces in The Cut about soft boys and their thrifted cardigans. He has become a punchline, a cultural trope; and yet, the very performance that makes him charming online is the very same performance that is survival for a woman. As American gender studies scholar Judith Butler puts it in their book Gender Trouble, “The effect of gender is produced through the stylization of the body and, hence, must be understood as the mundane way in which bodily gestures, movements, and styles of various kinds constitute the illusion of an abiding gendered self.” Gender is not naturally an inner truth we express but a socially constructed performance only sustained by constant “doing,” a performance women have had to uphold to dodge alienation and violence. Victorian women were taught music, embroidery, and language not for self-fulfillment but to increase marriage prospects; 19th and 20th century women writers wrote under aliases (George Eliot, Currer Bell) to gain publication and respectability; the Japanese geisha were a master of arts, conversation, and subtle seduction performed not for pleasure but for livelihood within a strict social hierarchy. A performance exists even behind your “sexy” Joan of Arc Halloween costume, a woman who dressed masculine for respectability and protection against sexual assault in her military ranks.

A woman who didn’t abide by gendered behavioral standards could be ostracized, raped, or branded a witch and burned at the stake, so we’ve become our own CCTV cameras, our own voyeurs. “You are a woman with a man inside, watching a woman,” Margaret Atwood writes in her novel The Robber Bride. We have trained ourselves to become the ‘Cool Girl,’ the one who’s easily digestible for the male palate. Gillian Flynn even wrote an entire monologue on this in Gone Girl: the girl who will guzzle shitty beer with you during Sunday night football, down hot dogs like it’s a competitive eating competition (but her waist is still the width of your pinky), and she always agrees enthusiastically to propositions of threesomes or anal sex. We must withhold anger at all costs and slap a cheesy smile on our face, but the performative man is taxing because he needs to carry the weight of The Bell Jar in his Trader Joe’s tote.

Or, more so, because his entire act is built on theft. Benson Boone croons ballads with mascara-stained lashes; Harry Styles struts in a Gucci dress on the cover of Vogue—and suddenly the cultural narrative applauds them as brave, edgy, visionary. But bell hooks already told us: the problem is not men experimenting with femininity, it’s that the credit and cultural capital always flows upstream to them. A woman wearing trousers in 1920 risked her livelihood; Harry Styles wears a tutu, and Twitter calls him “the future of masculinity.” I’d like to differ, but then again, the epitome of white masculinity is thievery, isn’t it?

This pattern is ancient. Even religion could not abide giving women ownership of creation: Genesis rewrites birth as man-made, a rib substituting for the uterus, the miracle of reproduction reframed so that men could claim authorship. It is our labor to remind them that they didn’t emerge from a single rib like some DIY Ikea project, that no deity drafted a blueprint with carpenter’s precision while we twiddled our thumbs. No, they came out of their mother’s womb after an agonizing eighteen-hour labor in stirrups she shouldn’t be in because King Louis XIV had a sadistic birthing kink.

And while these men supposedly read bell hooks and Simone de Beauvoir (even Adrienne Rich is too “underground” for their performance) their knowledge on feminist ideology is grossly lacking. I’ve encountered my fair share of performative men in the archaic times of my heterosexual dating, including the four horsemen of my own heterosexual apocalypse: the boy who carried tampons in his backpack, the boy who seduced by letting you lead in bachata, the boy who serenaded with cracking vocals on the guitar, and the especially notorious boy who showed me his Notes app poetry upon discovering I was a writer—poetry shockingly identical to Federico García Lorca’s Gypsy Ballads. A sociopath, a slut-shamer, a pathological liar, and a narcissist, respectively (I had quite the taste, I know). But despite their performance of the sensitive, smart, feminist man, none of them could contribute to any discourse beyond abortion rights.

Men’s engagement with feminism often aligns with neoliberal ideals, presenting a version of feminism that is palatable and convenient until it challenges their own privileges. As sociologist Angela McRobbie observes in “Notes on the Perfect,” this form of feminism is “made compatible with an individualising project and is also made to fit with the idea of competition,” where the focus shifts to personal empowerment and choice, sidelining structural inequalities. The performative man I had the displeasure of meeting in Barcelona fought tooth and nail for “choice” feminism, yet drew a blank when I mentioned Marxism and intersectionality, terms so basic to any political discourse. This privileged ignorance reveals the limits of men’s commitment to feminism, supporting it only when it poses no real threat to their power nor the societal structures that provide them bountiful benefits. The performative man is a “feminist,” but when you mention large-scale systemic change, he shivers in his black leather Chelsea boots he thrifted in Berlin before you even knew who Phoebe Bridgers was. And that’s how I become this extreme feminazi because I condemn plastic surgery and the abuse of GLP-1 medication, words that provoke a self-proclaimed “choice” feminist man because it insinuates the dismantling of the very institutions which spoil them.

Fashion remains the performative man’s safe playground, where he can slip femininity on like a costume, preen for applause, then fold it neatly back into his closet before bedtime. He’ll curate antique rings and oversized cardigans like a museum exhibition, each look a carefully performed gesture signaling taste, sensitivity, and rebellion—but always one step away from risk. The performative man can play with femininity as an accessory and shortcut to cultural cachet, wearing eyeliner like courage without ever facing the cost women have paid for the same expression. He’ll read Didion and call it profound, but if Anaïs Nin ever crossed his desk, she’d be an abhorrent whore. Performance or not, he is still a man.