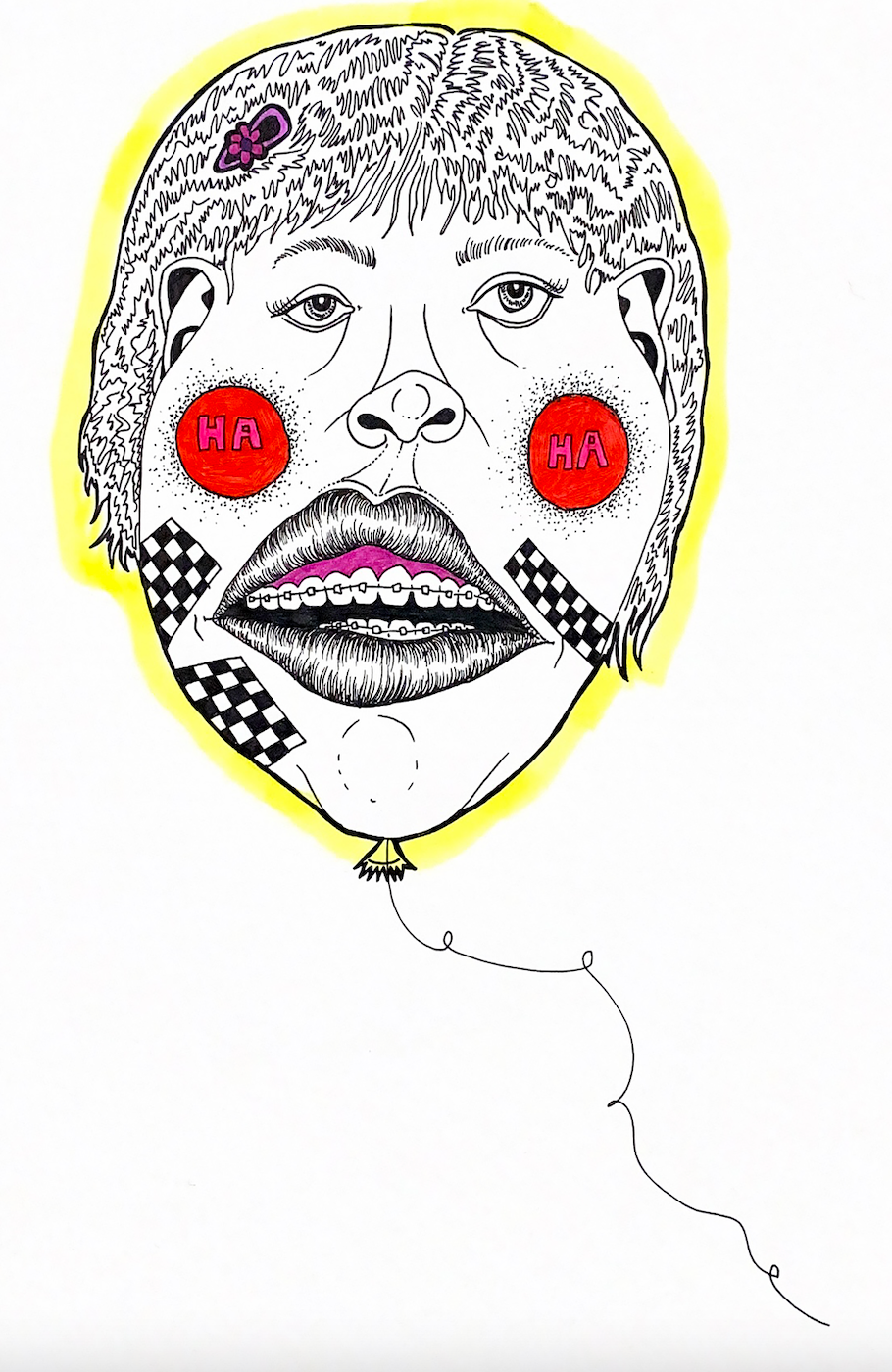

I Know I'm Funny, Ha Ha

I don’t know if men are aware that I know I’m funny, or if they think that doesn’t matter since they have yet to validate it. But I know I’m funny. It would be a bit odd if I didn’t, considering that working toward a degree in comedic arts with the intent of pursuing a career in the field is my very purpose for attending this institution.

And the more I’ve come to think about it, I’ve realized men have only really noted that I’m funny. It seems as if they believe an excess of praising my humor could make up for a lack of compliments on all other fronts. That over-addressing my wittiness could conceal the fact that that’s all they see in me. I find it rather difficult trying to recall the times in which men have called me beautiful, or pretty, or at the very least, attractive. But there seems to be no lack of recognition of my hilarity. This isn’t to say that I am so sure of my humor that I no longer wish to be reassured of it. But rather, I am cautious when accepting the praise on the count that too many times, the phrase has been a thinly veiled jab.

Similarly, senior writing, literature, and publishing student Kate Healy ‘23 has picked up on this pattern. She notes, “I think that men are always shocked that I am more than my size. It’s always the second conversation I have with a man where I make him laugh, and he looks at me, pretending to see me for the first time, and tells me that I’m ‘actually really funny.’ I guess that ‘actually’ isn’t supposed to be as offensive as it is.”

Art by Natasha Arnowitz

The unfortunate truth is that this is not a unique experience. The harsh reality is that women who don’t fit the conventional beauty standard—women of color, plus-sized women, non-femme presenting women—are only complimented for their humor rather than outward appearance. And the implications of this are detrimental. It seems as if this pattern of rejecting intimacy for these women has translated into the use of them only as comedic relief. Disregarding that, just like any other person, these women are complex beings and possess a unique set of individual traits and qualities worthy of recognition.

By existing as anything other than what has been wrongly framed to be the ideal standard of beauty (slim, white, feminine) these women have unjustly been exempted from being deemed worthy of praise for their outward appearance. This places women of color, who don’t possess Eurocentric beauty standards, women with plus-sized bodies and bodies that deviate from the norm, and people with (rightfully) no desire to fit an ideal standard of femininity, at a disadvantage—and by no means of their own action. These women are punished for simply existing in their own bodies.

Xiara Glickell ‘25, a member of the sketch comedy troupe Chocolate Cake City, has noticed themself in this pattern as a non-binary person of color. They say, “Men think they’re put in a tough position when asked to compliment someone like myself. When a body like mine is not commonly the frame of reference for beauty, they refuse to challenge this idea and go with what they assume to be a ‘safe’ comment. They fall back on saying that I’m funny or witty or quirky.”

This isn’t to say this is a dire issue because women people aren’t being validated. Rather, this is a dire issue because women are being diminished. We see this diminishment through the ways in which these women are portrayed onscreen. The trope these women have been written into is the funny sidekick. Accompanying a skinny, white, conventionally pretty protagonist, the sidekick is often a woman of color and most commonly a plus-size woman. Often in these depictions, the main character’s love life is the focus of the plot, and the role in which the funny sidekick plays is to comfort her. Her entire existence is written to provide emotional support through the form of a witty joke or anecdote.

Take, for example, Sookie in Gilmore Girls, who takes a backseat to thin and quirky Lorelai Gilmore, Etta Candy in every adaptation of Wonder Woman, or Kat in Euphoria. While these characters may have been created with the good intention of showcasing plus-sized bodies, they have unfortunately become a walking joke. Fat women, in almost all portrayals, are still relegated to comedic relief or goofy sidekicks.

But this isn’t to say all portrayals are in poor taste. In recent years, a few creators have been more conscious in their depiction of plus-size women. More modern plus-size women have been rewritten to be strong, confident individuals who are aware of their bodies and regard themselves as desirable nonetheless. Think Donna from Parks and Recreation or Kelli from Insecure. These women are witty and humorous, but not at the expense of their size. Writers need to realize that when writing plus-size roles, the most important thing is to write them as genuine people with complex feelings. Their role goes beyond making us laugh.

So how do we combat the negative portrayals of these women? Simple: putting in the work to understand the experiences of the people who we write about. Writing about people from marginalized groups is hard, even for authors of that particular background, since so many people in the same communities can have a myriad of experiences. But this isn’t to say that it is more complicated to write characters from these communities. The reason accurate portrayals of these characters are so hard to come across is that whiteness has become the norm. Creators need to take the proper course of action to decolonize the media. Although it may be uncomfortable to confront that you’ve written a character that falls into a problematic trope, it is a necessary course of action. These characters can be funny without being your punchline.