The Art of the King Adaptation

The Art of the King Adaptation

Written By karenna umsheild

Art By Lauren Mallett

Stephen King infamously hates Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of The Shining. For all its glorious horror iconography and immortalized performances, he just cannot shake how inaccurate it is to the novel.

The relationship between King and Kubrick, between The Shining the book and The Shining the film, speaks to the fascinating dichotomy created between King’s stories and their cinematic counterparts. The relationships are complicated, different for each film, with a myriad of factors so complex that it is extremely difficult to determine whether one is simply good or bad. It’s one thing to make a good film, and another to make a good Stephen King adaptation; I am curious about where the intersections of this can be found, and what it says about storytelling methods in books and film. What can a filmmaker do with such rich, detailed prose? Do they need to search for substance?

Allow me to start with the best—The Shawshank Redemption is, to me, an excellent example of how an adaptation can also be an excellent film on its own. The original novella, Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption, tells an exceptional tale about hope and redemption through education, grit, and friendship. Director Frank Darabont transformed King’s excellent dialogue and prose into a film that celebrated the imagination and inspiration of the story, utilizing the best aspects of the work with the best aspects of the cinematic medium. Stand By Me is also a successful and very popular King adaptation that maintains the essence of the story, and is a part of the same novella collection as Shawshank, Different Seasons. Director Rob Reiner extracts the most powerful anecdotes, the most memorable scenes from the book and highlights those. He utilizes cinematic capabilities in making a film that captures the essence of King’s story while cutting out some of the less consequential moments.

The Mist, also directed by Frank Darabont, is a fascinating case because he does something really bold—he changes the ending completely to one that is far darker and more devastating than what King has written in his novella. The Mist has mixed reviews, largely for the poor CGI effects, but it still provides a really interesting example of a film adaptation celebrating the effective parts of King’s narrative—in this case, the character tensions and examples of religious extremism—while changing other aspects to make the film more powerful.

Misery is a different, yet fantastic example of a filmmaker using the horror capabilities of filmmaking to enhance the terror already in the story. Rob Reiner (who previously directed Stand By Me) takes the captivating, intense essence of King’s thriller and makes it as filmically terrifying as possible—with a chilling, unforgettable performance by Kathy Bates, a jumpy, intense score, and dramatic effects with light and scenery whenever possible. The film still lacks some of the gore, as well as the psychological terror in the protagonist’s mind, but it keeps the essence of the film which still allows for a very successful adaptation.

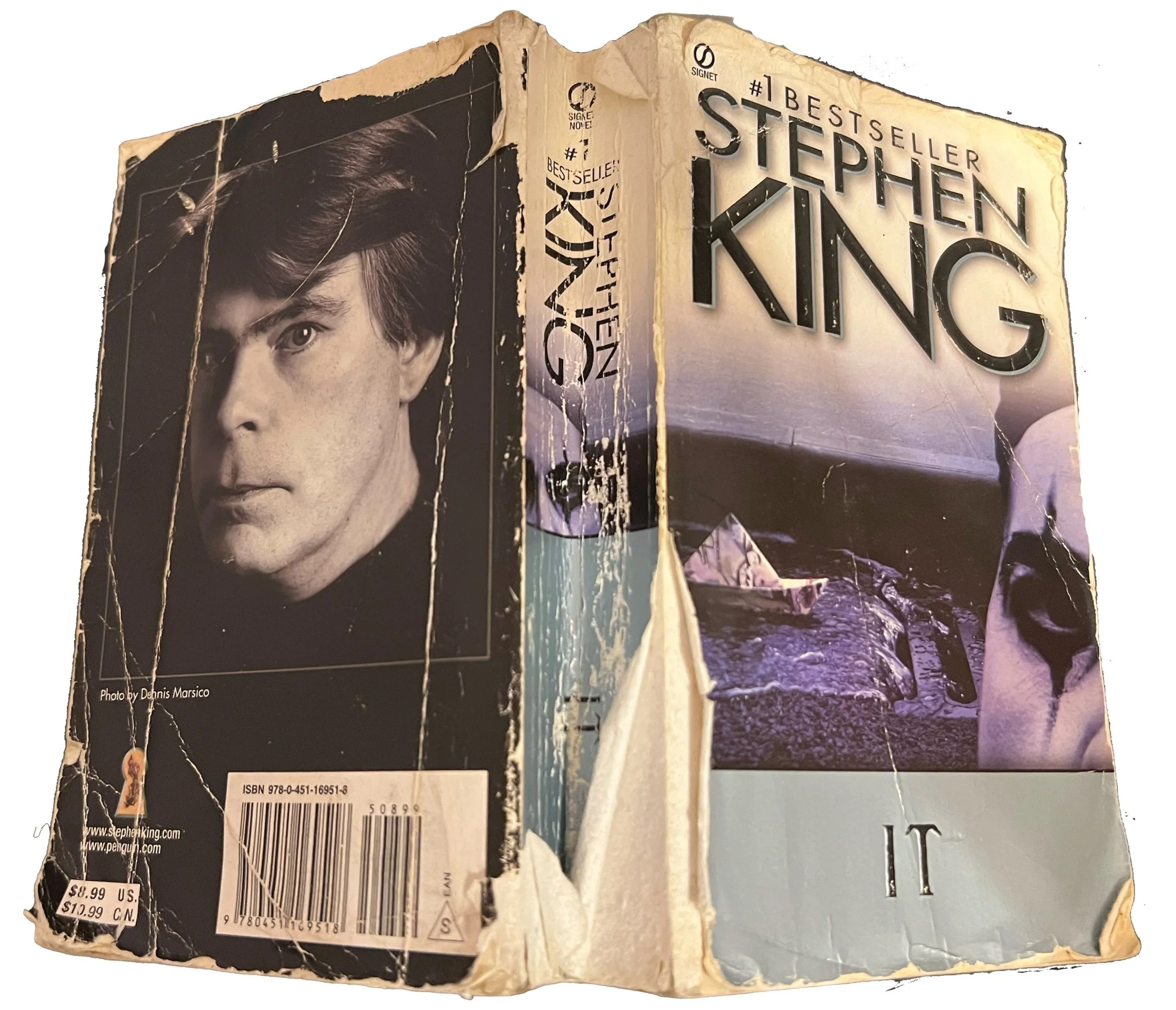

It is an interesting case, being adapted twice—27 years apart, in a keen homage to the lore of the novel—and neither adaptation being exceptionally accurate or successful. It creates a case for the idea that not all of King’s works are meant for the screen. The climax of It spans back and forth between the protagonists as children and adults, fighting Pennywise in his true form as a gigantic spider inside his mind, and performing an indigenous ritual in order to fight him in the Macroverse which was created by Maturin, the turtle that created the universe. The abstract, fantastical nature of the climax of the story makes it extremely difficult to adapt—but the colorful scares and shapeshifting powers also make it enticing to horror filmmakers and audiences. It is the story that walks this delicate line between a King adaptation and film, settles in between being appealing to filmmakers and audiences (even if for just how terrifying Pennywise looks), and being too dense and difficult a story to properly adapt.

Doctor Sleep posed a fascinating challenge to filmmaker Mike Flanagan, for not only was he adapting a King work, but a sequel to The Shining. Flanagan had to delicately split the difference, to offer an adaptation that is true as a sequel to the original Shining novel, and as a sequel to the film adaptation. Doctor Sleep is imperfect, but it is well-acted and well-made, and it manages to be faithful to its novel counterpart with visual homages to The Shining film that marries what makes both works so enamoring. It honors King’s storytelling by not shying away from grisly details and immersing into his visceral characterization, and uses the timelessness of film visuals to honor the thrills of Kubrick’s film.

The best King adaptations are carefully chosen—often his shorter works, less dense yet still rife with prose and inventive stories—and the most emphatic parts are made even more visceral through the power of film. These examples (and many others not listed) examine the art of adaptation and film through a storyteller both universally lauded and frequently criticized. Yet for any criticism he has received, he remains a central figure in horror storytelling. His works provide a stage for nuance and subjectivity, for creativity that emerges from itself and all the avenues in which his work, even when surface-level or brilliant or obscure, can exemplify the most fascinating elements of cinema and art as a whole.